Julia and Me (Part 3)

Believe in myself

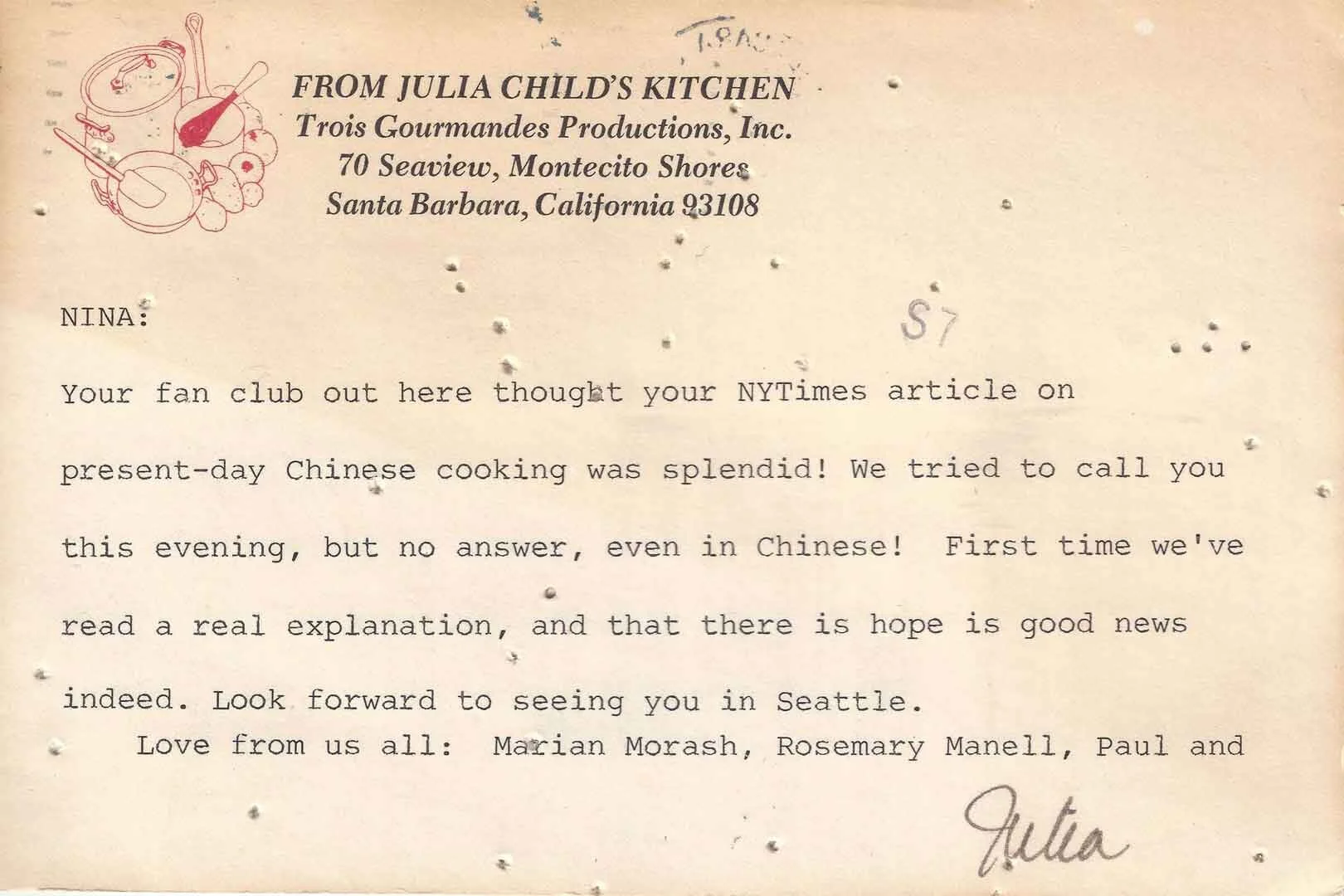

It was Julia who taught me how to believe in myself as an accomplished professional woman, especially in the most challenging of times of male domination in the industry. She showed me that my talent as an authority on Chinese cuisine was not only unique, but exceptional—a belief that served me well in all my future endeavors. Julia rarely gave endorsements because she knew the selling power of her name. Instead, she would constantly send brief messages of support on her personal post cards. (See above)

Around her 86th birthday, we met in a Cantonese seafood restaurant in Chinatown, Boston. Julia arrived, trailed by her close friend, master pastry chef, Jim Dodge, who was dragging a huge “Nebuchadnezzar” size bottle of Perrier Jouet Champagne that had been inscribed personally to Julia from the company on the occasion of her eighty-fifth birthday. It had been hanging around her house collecting dust for a year, so she had decided on the spur of the moment that we should all share it. It wasn’t properly chilled, but who cared? We drank and ate like Chinese emperors.

There are many other funny and memorable tales of experiences with Julia, but I would be remiss not to recount the one that demonstrates her rock-solid support of other food writers. It was in the late Eighties, and by then I had been a regular contributor to The New York Times Food Section for some eight years. Suddenly The Times demanded that all freelance writers sign a “work for hire” contract that would retroactively give them all rights to any articles or recipes we had not only written in the past but also going forward. This meant that we wouldn’t even be able to use our recipes for future cookbooks. For a food writer, this was tantamount to sabotaging our very livelihood. Adding insult to injury, we were already being paid very little despite the fact that all of us spent extra time and money testing recipes. The new contract didn’t offer additional compensation. The Times, of course, knew full well the prestige of having a NY Times byline, not to mention the exposure.

I was outraged. To his credit, Jacques Pepin, resigned, refusing to continue his weekly column out of protest, but many other writers were torn since they wanted to continue to write for the paper. I realized that if we could recruit a solid block of freelancers we might have better bargaining power, but after calls to several other well-known columnists, who refused to challenge the newspaper, I was frustrated and infuriated.

“It was Julia who taught me to believe in myself as an accomplished, professional woman, especially in the most at times of male domination in the industry.”

For some reason, I thought of Julia, who I felt might be sympathetic as she had never shied away from being outspoken about her opinions. I called her, explained the situation, and faxed her a copy of the offending contract. She, too, felt it was totally unfair. The following day she called a prominent publication and issued a strong statement criticizing the new policy. She later went to Washington to represent food writers and testify at a public hearing. As a result of the negative publicity and public support for the writers, The Times backed down and offered an alternative contract to those who had protested. We were given the option of co-owning our material. It was a huge victory for freelancers, particularly cookbook authors. We established a fair policy that was soon adopted by many magazines.

Cookbooks

Nina is the author of numerous award-winning cookbooks.